All kids — like all humans — get angry.

Anger is the body’s “fight” response. It’s designed to protect us when we feel threatened or when someone crosses a boundary that matters to us.

But we don’t only get angry in response to what’s happening right now. When something in the present reminds us of an older hurt, fear, or helplessness, our nervous system can react as if the past is happening again — even if today’s “threat” is actually small. That’s why a three-year-old’s defiance can light up a parent’s rage.

We also use anger to defend against more vulnerable feelings. When fear, hurt, disappointment, pain, or grief feels too scary to feel, we tend to lash out instead. Anger doesn’t make the hurt go away, but it can temporarily numb the pain and make us feel less powerless. (That’s one reason anger often shows up as part of the grieving process.)

So humans mobilize against any perceived threat — even the threat of our own upsetting feelings — by going into protection mode, which often means going on the attack.

That’s true for kids, too. And because children don’t yet have much perspective, a small disappointment can feel like the end of the world. Worse, they don’t yet have a fully developed frontal cortex to help them self-regulate, so they’re even more prone to lashing out when they’re angry. (It’s a little wild that we expect children to handle anger constructively when so often we adults don’t.)

Sometimes attacking makes sense when there’s a real threat. But that’s rare. Most of the time, when kids get angry, they want to attack:

- their little brother (who broke their treasured memento),

- their parents (who disciplined them “unfairly”),

- their teacher (who embarrassed them),

- or the playground bully (who scared them).

Luckily, as children’s brains develop, they gain the capacity to manage anger constructively — if they grow up in a home where anger is handled in a healthy way.

What does “constructive” anger look like?

1. Controlling aggressive impulses

When parents accept and empathize with a child’s emotions, the child learns that feelings aren’t dangerous. They can be felt — without necessarily being acted on.

As you accept your child’s anger and stay calm, your child builds the neural pathways and emotional skills to calm herself and communicate how she feels without hurting people or property. By kindergarten, most kids can tolerate the surge of adrenaline and other “fight” chemicals in the body without acting on them by clobbering a playmate. (Note: It’s not unusual for kindergartners to still hit siblings.)

2. Acknowledging the anger — and the more vulnerable feelings underneath

If you can keep yourself from getting triggered, and can acknowledge why your child is upset, his anger will begin to soften. That helps him feel safe enough to notice the more vulnerable emotions driving the anger.

Once your child can allow himself to feel his grief over the broken treasure, his hurt that you were unfair, his shame when he didn’t know the answer in class, or his fear when a classmate threatened him, those feelings begin to heal. As those vulnerable feelings fade, he no longer needs anger to defend against them — and the anger dissolves.

By contrast, when children don’t feel safe enough to experience the underlying emotions, they keep losing their tempers—because they don’t have another way to cope with what’s going on inside. These are the kids who can seem to have “a chip on their shoulder.” They lug around resentments — a sense that life is against them — and they’re always ready to get angry.

3. Constructive problem-solving

Over time, the goal is for your child to use anger as information and energy to improve a situation so it doesn’t keep happening.

That might mean moving treasures out of little brother’s reach, getting parental help with a bully, or practicing a skill (like coming to class prepared). It can also include acknowledging your child’s own contribution to the problem — so they resolve to do better next time.

With your help, your child learns to calm himself when he’s angry, express his needs without attacking, see the other person’s point of view, and look for win/win solutions — instead of assuming he’s right and the other person is wrong.

This takes years of guidance. But when parents help kids feel safe enough to express anger and explore what’s underneath it, children gradually gain more control. During the grade-school years, they become increasingly able to express anger appropriately and move into problem-solving.

How can parents help kids learn to manage their anger?

Here are ten tips for teaching your child healthy anger management in everyday life.

1. Start with yourself

You’re probably good at staying calm when things are going well. What takes heroic effort is staying calm when things get turbulent.

But yelling at an angry child reinforces what she already feels: that she’s in danger. (You may not see why she would feel “in danger” when she just socked her little brother — but a child who is lashing out is a child who feels threatened and defensive.) Your anger will only make the storm worse.

If you’re in the habit of shouting, know that you’re modeling behavior your child will copy. It can be tough to stop yourself from yelling, but if you give in, you can’t expect your child to learn self-control. Children learn by watching us handle disagreement and conflict.

2. Get good at de-escalating

Your job when your child is angry is to restore calm — because kids can only learn and make better choices when they’re calm.

Your steady presence, even when your child is furious, is what helps them feel safe. That sense of safety is what helps build the brain pathways that shut off the “fight or flight” response and allow the frontal cortex — the “reasoning brain” — to come online.

This process where your child "borrows" your calm is called coregulation, and it is the foundation of your child's emerging ability to self-regulate.

3. Remember: all feelings are allowed

When humans are angry, they don’t calm down until they feel heard. So when your child expresses anger, your first job is to listen and acknowledge how upset he is and why. You don’t have to agree with his reasons to recognize that he’s angry — and that his feelings matter.

So in the moment, don’t tell your child to calm down or act appropriately. That usually escalates things, because your child tries harder to make you hear.

Instead, open the door to communication:

“You must be so mad to speak to me that way. I want to hear this. Can you tell me so I can hear — without yelling at me?”

Later, once your child has calmed down, you can talk about tone and language:

“You were so angry earlier that you yelled at me. I always want to hear when you’re upset, and I will always try to help. You never need to yell at me to get me to listen. Right?”

Often at this point, since your child now feels heard, they will spontaneously apologize.

You’re not encouraging bad behavior. All emotions are acceptable; only actions need to be limited. When we ask kids to “stuff” their feelings, those emotions don’t disappear — they go underground, outside conscious control, and then pop out unregulated. If feelings are allowed, the child can accept them instead of repressing them. That gives enough inner control to put them into words rather than fists. Over time, verbal expression becomes more modulated and appropriate.

4. Give your child ways to manage angry impulses in the moment.

Kids need concrete skills for the moment anger hits. When your child is calm, make a list together of constructive ways to handle big feelings. Let him do the writing or add pictures so he feels ownership. Post the list on the refrigerator — and model using it yourself:

“I’m getting annoyed, so I’m checking our MAD list… Oh — I think I’ll put on some music and dance out my frustration.”

Here are some ideas to get you started:

- Teach a “PAUSE” breath: inhale through the nose for four counts, exhale through the mouth for eight.

- Grab two squishy balls; hand her one and demonstrate squeezing out frustration.

- Put on music and do an “angry dance.”

- To keep from hitting, kids can wrap their arms around their body (each hand on the opposite shoulder) and yell something like “MOM!” or “STOP!”

- Younger children often find it helpful to stomp. Don’t worry — it’s better than kicking a sibling or the wall, and over time they’ll shift into words.

- For older kids: draw or write what they’re angry about, then rip the paper into tiny pieces.

One note about physical expression: what heals isn’t acting out aggression (which can actually intensify anger by signaling “emergency!”). The body may benefit from discharging tension — dancing is great for that. But what’s most helpful is that your child gets to show you how upset they are and feel understood. If your child wants to clobber something (instead of a person), you can say:

“You are showing me just how mad you are about this! I see. Wow.”

5. Help your child notice her "warning signs."

Once kids are flooded with adrenaline and other “fight or flight” chemicals, they truly feel it’s an emergency. At that point it’s very hard to reach them; managing impulses is almost impossible. All we can offer is a safe haven while the storm sweeps through.

But if you help your child notice early signs and practice calming, she’ll have fewer blow-ups.

When she’s little, you’ll spot cues and intervene — a snuggle break, a snack, leaving the grocery store. As she gets older, you can coach awareness:

- “Sweetie, you’re getting upset. We can make this better. Let’s all take a deep breath and figure this out together.”

- “I know this is hard. And you can handle this. I’m here to help.”

6. Set firm limits on aggression.

Allowing feelings does not mean allowing destructive actions. Kids should never be allowed to hit others, including their parents. When they hit, they’re asking you to set limits and help them contain the anger.

Say:

“You can be as mad as you want, but no hitting. I will keep us all safe. You can tell me how mad you are without hurting.”

Also don’t let kids break things in their fury. That only adds guilt and a sense of being “bad.” Your job is to be a safe container while you witness the upset.

7. Don’t send your child away to “calm down” alone

When your child is angry or upset, your goal is to restore a sense of safety — and that requires your calm presence. Kids need your love most when they “deserve it least.”

Instead of a “time out,” which leaves a child alone with big scary feelings, try a “time in,” where you stay close and help your child move through the upset. You’ll often see more self-control emerge over time, because your child feels less helpless and alone.

You don’t have to say much:

“I’m right here… You’re safe… I’m listening…”

Here is a post on Cozy Corners and Co-regulation to Calm Your Child

8. Restore connection.

Your child needs to know you understand and you’re there to help. If you know what’s going on, name it:

- “You are so angry that your tower fell.”

If you don’t know, describe what you see:

- “You’re crying so hard… I see how upset you are.”

Give permission:

- “It’s okay. Everyone feels mad (or sad) sometimes. I’ll stay right here while you show me your sads and mads.”

If your child will accept touch, offer it:

- “Here’s my hand on your back. You’re safe. I’m here.”

If he yells for you to go away:

“I hear you saying ‘go away,’ so I’m moving back — right over here. I won’t leave you all alone with these big feelings. I’ll be right here when you’re ready for a hug.”

9. Do preventive maintenance for the feelings that pile up each day

Every parent benefits from building a few emotion-coaching habits into daily life — practices that help your child feel safe and connected, and help her process the inevitable upsets that come with being a kid.

Key practices:

- Empathy: Respond with empathy and respect even when you set limits. (You won’t manage this 24/7 — just work on increasing your ratio.)

- Special Time: At least 15 minutes daily of one-on-one time with each child.

- Routines: Predictability helps kids feel safer.

- Make room for tears: Accept all emotions, and make it safe to cry.

- Snuggle time: Morning, bedtime, and as needed in between.

- Roughhousing and laughter: Aim for a daily chance to belly-laugh for at least 10 minutes, ideally with physical play.

Here's a whole post on preventive maintenance.

10. Help your child develop emotional intelligence — and get support when needed

Kids who feel comfortable with emotions are better able to manage anger constructively. There’s a whole section on this website on emotional intelligence.

Some kids, unfortunately, don’t feel safe expressing uncomfortable feelings. Maybe tears were discouraged, feelings were ridiculed, or they were sent away to “calm down” without help. Sometimes grief or fear feels too overwhelming. When vulnerable feelings are pushed down, they tend to pop out sideways — like sudden hitting from an otherwise loving preschooler.

These kids live in fear of their feelings. To defend against that fear, grief, or pain, they get angry — and they stay angry. If this is happening, a child may benefit from professional help.

How do you know when your child needs help handling anger?

Look for these signs:

- She can’t control aggressive impulses and hits people (other than siblings) past age six.

- Frequent explosive outbursts — like he’s carrying a full emotional backpack of upsets.

- She is constantly reflexively oppositional (and she isn’t two).

- He never acknowledges his role and feels chronically victimized or “picked on.”

- She frequently loses friends, alienates adults, or is constantly in conflict.

- He seems preoccupied with revenge.

- She threatens to hurt herself physically (or does).

- He damages property regularly.

- She repeatedly expresses hatred toward herself or someone else.

- He hurts animals or smaller children who are not siblings.

When a child has “anger management issues,” it usually means he’s terrified of the feelings under the anger (fear, hurt, grief). To defend against emotions that feel unbearable, he hardens and clings to anger as armor. That “chip on the shoulder” can look like pushing you away — but it’s really a cry for help.

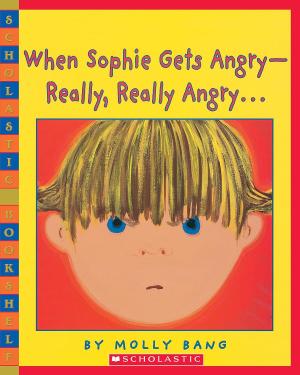

Start by using the ideas in this article to support your child, and begin talking more about emotions at home (the books below can help you start those conversations). If you don’t see change after a couple of months of steady effort, consider professional support.

In general, I recommend that parents go into counseling along with their child. You don’t want your child to feel broken and taken somewhere to get “fixed.” You want the whole family to learn new ways to communicate so everyone feels loved and gets their needs met. A good therapist who meets with you and your child together can help you do that.

Recommended Resources

PLEASE NOTE: These books are Amazon links with photos of the books. If you are not seeing them on your page, it may be that your browser is not picking them up. Please try a different browser. Enjoy!